'When Belgium was subdivided into four language areas in 1962, Brussels became officially bilingual.'

10 questions - 9. Why is Brussels bilingual?

9. Why is Brussels bilingual when only a minority of Dutch speakers live there?

Why is English not an official language in an international city such as Brussels?

Brussels is bilingual: French and Dutch are the official languages there. Yet Brussels is home to only a minority of Flemish people. This may sound strange, but the reason is simple. For centuries, Brussels was a Dutch-speaking city and today it is still the capital of Flanders.

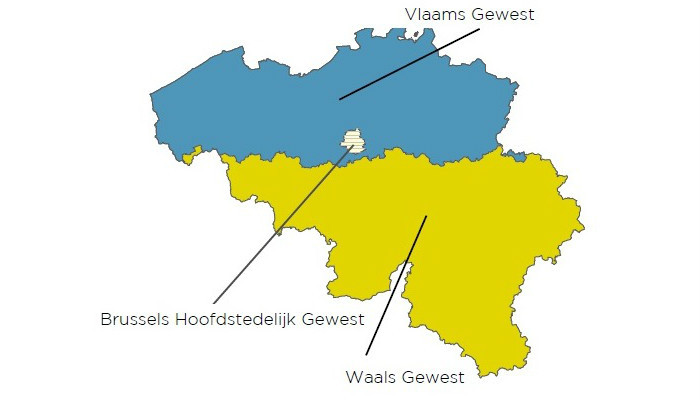

BRUSSELS-CAPITAL REGION*

The nineteen Brussels municipalities together form the Brussels-Capital Region. Brussels-Capital is one of these nineteen municipalities as well as the capital of Flanders and Belgium. The Brussels-Capital Region has been officially bilingual since the subdivision of our country into language areas. However, Brussels is enclosed in Flanders, of which it is also the capital.

By making Brussels the capital of Flanders and establishing the Flemish Government, the Flemish Parliament and the administration there, Flanders has opted to emphasise the close relationship between Flanders and Brussels. However, Brussels is also the capital of Belgium and Europe and has consequently grown into a multicultural metropolis. Thirty per cent of the more than 1 million residents are foreigners. Although Brussels is officially bilingual, in reality it has been multilingual for a long time. It goes without saying that the Flemish minority (including the hundreds of thousands of commuters travelling from Flanders to Brussels each day) have the right to be helped in its own language here. The many foreigners living in Brussels on the other hand cannot expect this, or even the right to use English, which sometimes causes resentment. This can be explained partly through history, partly through politics.

* The map can be found in English in the pdf brochure

FROM A DUTCH-SPEAKING TO A MULTILINGUAL CITY

Historically speaking, Brussels is a Dutch-speaking city. From its creation in the tenth century until the eighteenth century Brussels was almost exclusively Dutch-speaking. In the nineteenth century, following the independence of Belgium, the language relations changed. Because Belgium chose French as its official language, the French language started to dominate public life and it became the language of the courts, administration, army, culture and media. As the language of the political and economic elite, the French language developed into a status symbol.

As the new capital, Brussels experienced a population explosion. In 1830 Brussels had 50,000 inhabitants. In 1875 this grew to 250,000 and in 1914 to 750,000. As the political, financial and economic centre Brussels had a French-speaking upper and middle class. Because primary and secondary education was only provided in French, the French language gradually also permeated the lower social classes. The many immigrants, most of whom originated from Flanders, were forced to speak French if they wanted to climb the social ladder. This caused the Frenchification of Brussels to continue at a rapid pace.

OFFICIALLY BILINGUAL

When Belgium was subdivided into four language areas in 1962, Brussels became officially bilingual. The bilingual area continued to be limited to the nineteen municipalities that formed the Brussels metropolitan area. In 1989, the borders of Brussels and its bilingual status were re-confirmed. This was done with a special parliamentary majority. In both chambers of the federal parliament two thirds of the MPs adopted the law with a majority in both the Dutch-speaking and French-speaking language groups. Since the Flemish are in the minority in Brussels, so is their political representation in the capital. Today, the Flemish have a guaranteed representation in the Brussels parliament. When a Brussels municipality appoints a Flemish alderman/alderwoman, it receives additional funds.

ENGLISH AS FOURTH NATIONAL LANGUAGE?

Because of the large number of foreign speakers, some suggest the idea of introducing English as the fourth national language. This would allow the many international residents in Brussels to be addressed in English. Although this may seem advisable for the international community, it seems unfeasible both practically and politically. In fact, Brussels and its public services are already struggling with the current bilingual status.